Home > Resources > Jarie Bolander | Ride or Die: Loving Through Tragedy, A Husband’s Memoir

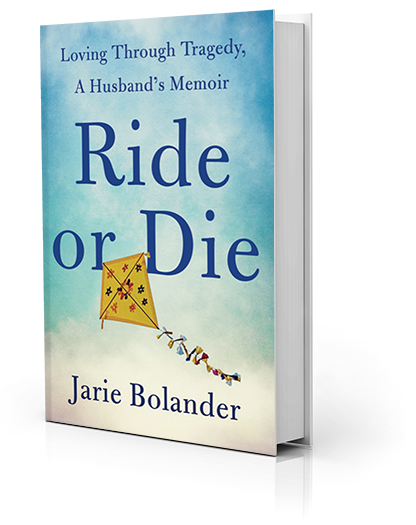

Ride or Die: Loving Through Tragedy, A Husband’s Memoir

by Jarie Bolander, SparkPress (2023)

Jarie Bolander wrote this raw, heartfelt tribute to his wife, Jane. He chronicles her illness and his experience in order to help men and the people who love them through their loss and grief. Ride or Die offers a detailed exploration of Jarie’s experience of grief, in the hopes that others suffering through it will not feel so alone. The book, out this fall, takes the reader through intimate conversations and thoughts of a “Gen-X latchkey-generation husband”—a man who has always had to fend for himself and believed that it’s up to him to solve his own problems—as and after his wife, Jane, succumbs to a terminal disease.

Excerpt:

Fear and Loathing

A couple of days after our tearful FaceTime chat, Jane started to feel better. No one ever explained what had made her so sick. I was glad it was behind us and that I felt well enough to be with her.

I easily fell back into the monotonous hospital routine—breakfast, lunch, dinner, blood draws, and bedding changes on a regular schedule, which we actually looked forward to because it marked the passing of another day. The feeling was similar to running a marathon when what keeps you going is getting to the next water stop, and the next, and the next. Keep going, you tell yourself, it will be over soon. But, of course, with cancer you wake up the next day and you’re Bill Murray in Groundhog Day—same faces, same places, same cornbread chicken.

The grind of boredom made it hard to focus, but we gradually got used to it. I sometimes worked from the hospital room, but the Internet was so slow that it was impossible to get much done. We knew all the chemo nurses, learned to anticipate their shift changes, and figured out what the CBC numbers meant. My favorite escape (besides the secret stairs) was the Panera up the street from the hospital, which provided two things that made me happy: double espressos and orange-glazed scones. Sometimes I’d sneak Jane a spinach and bacon egg soufflé, dutifully microwaved to kill any possible contamination. A feast.

Becoming the caregiver for your spouse was what the “in sickness” part meant in marriage vows. Of course, there are variable degrees of “in sickness,” and most couples might switch between partner and caregiver for maybe a day or two, two or three times a year. With an illness like leukemia, the switch was abrupt and total—not unlike what it must feel like when a newborn comes into your life. The caregiving was something that you could get used to since if you honored your vows, you had no choice. The tricky part was dealing with other people, especially random people.

I didn’t blame people for not knowing what to say or focusing just on the sick person. I did blame them for standard responses like, “Things always happen for a reason,” or “It’s God’s will.” So many platitudes take no account of the realities someone in crisis is going through. But I’m afraid I’ve used similar phrases myself to avoid real, gut-wrenching conversations. We all do.

How do you talk to someone who is watching their spouse or partner battle a life-threatening disease? How do you comfort someone whose child, sibling, or parent died? I still don’t have all the answers. For me, this experience was so painful that I hoped I would wake up one day to find it was a bad dream. I fantasized about the sun rising on the day Jane was cancer-free. In the evening we could go out to a real restaurant for a romantic dinner. The night I could touch my wife again or kiss her without fear that I would make her sicker.

I was becoming isolated and lonely, as if I were watching a movie about my life, not living it. It was hard to cope with the loneliness and the loss of intimacy. That’s why I would fill the void with caffeine, sugar, and CBD. It gave me the needed hit of dopamine that I couldn’t get anywhere else. I also figured out how to handle the requests for help. I’d say, “I’ll get back to you,” and never do so.

After a little over four weeks, it was finally time to go home from the hospital. We almost didn’t believe it. We had survived the first round of chemo. By a minor miracle, we hadn’t killed each other or the staff.

Chemo causes something called “chemo brain,” which makes people forgetful and irritable. Mix that with feeling like shit because you can’t sleep and have mouth sores, a stomach lining that’s half gone, and the hot flashes of premenopause, and you can see why cancer patients are offered Ativan for anxiety. The world felt like it was slowing down, making ordinary frustrations

hard to handle. Patients are often on a fistful of drugs to resolve some of these problematic side effects of treatment. Jane was on antifungal, antibacterial, and antiviral meds, along with Tagamet to keep her heartburn at bay. I couldn’t imagine what she would be like without them.

“When can we go? I’m sick of being here. Go ask them again!” She was impatient and pacing around the room in her favorite pair of sweatpants, a white tank top, matching zip-up hoodie, and her Nike workout shoes.

“I asked them ten minutes ago. They’re waiting for the discharge paperwork.” I was checking email, trying to keep up with all the work.

“Go ask again. You have to fight for things. Be my advocate. Stop being so nice. You do this all the time, letting people roll over you.” Jane was more irritated than usual.

“That’s not true. How many times do I have to ask?” I raised my voice. Her complaints were getting old. “I want to get out of here too, you know. Do you think I like sleeping here?”

“I want you to keep asking until we actually get out of here. I want to go home.” She started to cry. “I want to feel normal, be in a normal bed, eat normal food. Please.”

The mood swings were getting worse, and there was nothing to do but comply. I headed into the hallway and made a list in my head: Ativan to calm her down, liquid Benadryl to knock her out. We also needed some chocolate-covered blueberry edibles. Jane loved those, and they always put her in a better mood and helped her appetite.

I could feel her hovering as I stepped toward the doorway, urging me along, so I turned around. Taking her in at that moment was a punch to the gut. She’d changed in just a month. She was thinner but also bloated, mumbling to herself as she paced around. I told myself it was going to be better when we got to Walnut Creek, with more people to help, more familiar surroundings.

I made my way toward the nurses’ station. I forced myself to take a deep breath. Don’t take anything personally. Focus on the task at hand. Don’t take no for an answer. Be that guy—the dick who always gets his way. The one you hate.

Before I even opened my mouth, the discharge nurse handed me a stack of papers and a bag of drugs. “You guys are free to go,” she said. “Do you need a wheelchair?”

“Um. Sure. I can take this one.” I gestured toward a shiny chair nearby.

“Works for me.”

I triumphantly returned to our room with the wheelchair, papers, and drugs, in a better mood. “We’re all set. We can go now.” I was actually smiling.

Jane was not smiling. “It’s about time. What took so long?”

“Took so long? I was gone for less than three minutes!” I said. “Let’s get going. Let me make sure we have everything. I don’t want you to have to come back any time soon.”

I double-checked the bag Jane had already triple-checked. I would give anything to never come back here, but I knew that was wishful thinking.