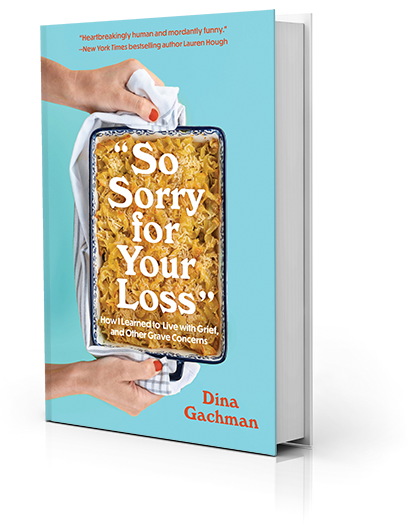

Home > Resources > Dina Gachman | “So Sorry for Your Loss”: How I Learned to Live with Grief, and Other Grave Concerns

“So Sorry for Your Loss”: How I Learned to Live with Grief, and Other Grave Concerns

by Dina Gachman

Dina Gachman is an award-winning journalist, Pulitzer Center grantee, and frequent contributor to The New York Times, Vox, Texas Monthly, and more. She’s a New York Times best-selling ghostwriter and the author of Brokenomics: 50 Ways to Live the Dream on a Dime. She lives near Austin, Texas, with her husband and son.

Excerpt from Chapter 1: This Is Not a Detour:

The second phone call that launched me into deep grief happened on a Monday night. It was March 1, 2021, and our plane had just touched down in Austin. I was with my husband, Jerett, and our three-year-old son Cole, coming back from visiting my in-laws in Florida. If you’ve ever flown with a kid, maybe you can imagine my state of mind at that moment: frazzled, tense, and teetering on the edge of releasing a bloodcurdling scream. My hair was a tumbleweed and I was covered in half-eaten snacks.

Adding to my stress was the fact that, before our plane took off that day, I knew my sister Jackie was in trouble. She was so often in trouble, in and out of detoxes and rehabs, picked up by ambulances after being found on lawns or sidewalks by her kind neighbors in Queens, who were two married ex-cops who had probably seen their share of people passed out all over New York. I never met those neighbors, but I talked to them on the phone, listening as they explained that she was drunk again. Incoherent again. On her way back to detox, yet again. I would thank these strangers for doing what I could not, from so far across the country. This type of scenario happened so many times over the years, with different neighbors or friends or random acquaintances of Jackie’s, that I cannot begin to count. Even so, she always managed to pull through, at least for a little while. I used to joke with my other sisters, Amy and Kathryn, that Jackie would outlive us all. She had nine lives, like a cat. It was our way of convincing each other, and ourselves, that she’d be okay.

This time around, while I was on that trip with my in-laws in Florida, Jackie had been missing for a few days, after nearly a year of sobriety. I was so relieved that she had finally gotten sober again right as the pandemic hit New York. During the winter of 2020, imagining her wandering through the streets and subways not sober, maskless, scared me.

Whenever Jackie disappeared in the past, it was usually a day or two, but she would always, without fail, contact our dad. She told him everything, and he always listened, never judging or scolding her, always trying his best to understand and encouraging her to get help. This time even he hadn’t heard from her and neither had her husband, Niall. Thankfully, the morning of my flight back to Austin, we finally got a call from the police, saying they had found her in a motel in a small Colorado town, where she and Niall had recently moved to escape the chaos of New York and start a new life. When my plane landed back home in Austin, that’s all I knew: They had found my sister. I figured the next call would be from my dad telling me that Jackie was back in detox. He would give me the number of the hospital so I could call her and tell her I loved her, and to please get help, again.

As the plane moved toward the gate, I brushed away some stray Cheerios and checked my phone. I saw a text from Amy: I can’t believe this is real. “I need to call Amy,” I told Jerett. My heart constricted, or at least it felt like it constricted. If you think that’s dramatic, the Old English word for grief, heartsarnes, means soreness of the heart. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, a legitimate medical condition, is a temporary weakening of the heart’s main pumping chamber, which can make you feel like you’re having a heart attack. It’s also called broken-heart syndrome, and clinically referred to as stress cardiomyopathy. Some experts suggest that it is caused by a surge of hormones associated with the fight-or-flight instinct, such as adrenaline. Anyone who has experienced the sledgehammer of grief understands that your chest actually hurts. The physical pain can be shocking, the way our bodies process our emotions, pulverizing us, pinning us to that exact moment in time. I had felt this pain before. Like broken-heart syndrome, grief is not a simple thing to diagnose, but I recognized that heart-pounding dizziness when it came for me again.

“Why don’t you wait to call Amy until we get home?” There was nothing casual about the way Jerett said this. His tone was tentative, a little too cautious. I didn’t even have to look over at him to realize that he knew something I did not. As Jerett tried to keep Cole from leapfrogging out of our seats while we waited for people to deplane, I stared at Amy’s text:

I can’t believe this is real.

All the forces in the world could not have stopped me from dialing Amy’s number. So I did.

“You can’t believe what’s real?” I asked before she could say hello. “The police said they found her this morning, right?” I knew, in my bones, what she meant, and what she couldn’t believe. I just wanted so badly to be wrong. I wanted nine lives for Jackie, ten, as many as it took.

Through tears, Amy explained that she and my dad and Kathryn had texted Jerett, telling him the news but begging him to keep it from me until we got home. Amy was so distraught that she forgot their pledge and texted anyway. We had been telling each other everything practically since the day she was born and I was three years old, and that’s a tough habit to break. The initial thought was that they didn’t want me to hear this news on an airplane, as if there is any good place to discover that your sister has died. Would a tropical beach with a mai tai in hand have lessened the blow? Maybe if I’d been on top of the Eiffel Tower at sunset, it wouldn’t have hurt as much? A claustrophobic plane with a feral three-year-old wasn’t ideal, but no place is. Amy said that they had found Jackie, but that hours later, they called back and told my dad, while he was at dinner with a friend, that his daughter, my sister, the third of his four girls, was gone.

Excerpted with permission from “So Sorry for Your Loss”: How I Learned to Live with Grief, and Other Grave Concerns. Text © 2023 Dina Gachman. Cover photo © 2023 Union Square & Co., LLC.