Home > Dying Unhoused

Dying Unhoused

by Loren Talbot

The unhoused population’s average life expectancy is 15 to 20 years lower than their housed counterparts.

Last month, INELDA’s executive director Douglas Simpson and I found ourselves in the 103-degree heat of Phoenix for the 2024 National Health Care for the Homeless Conference and Policy Symposium. I mention the heat because while we were able to participate in the conference due to the building’s air conditioning, I was regularly considering the people I saw unhoused situated on the hot pavement around the city during our stay. Death can occur anywhere and for many reasons, but as weather conditions exacerbated by climate change intensify, the needs for those experiencing homelessness are increased.

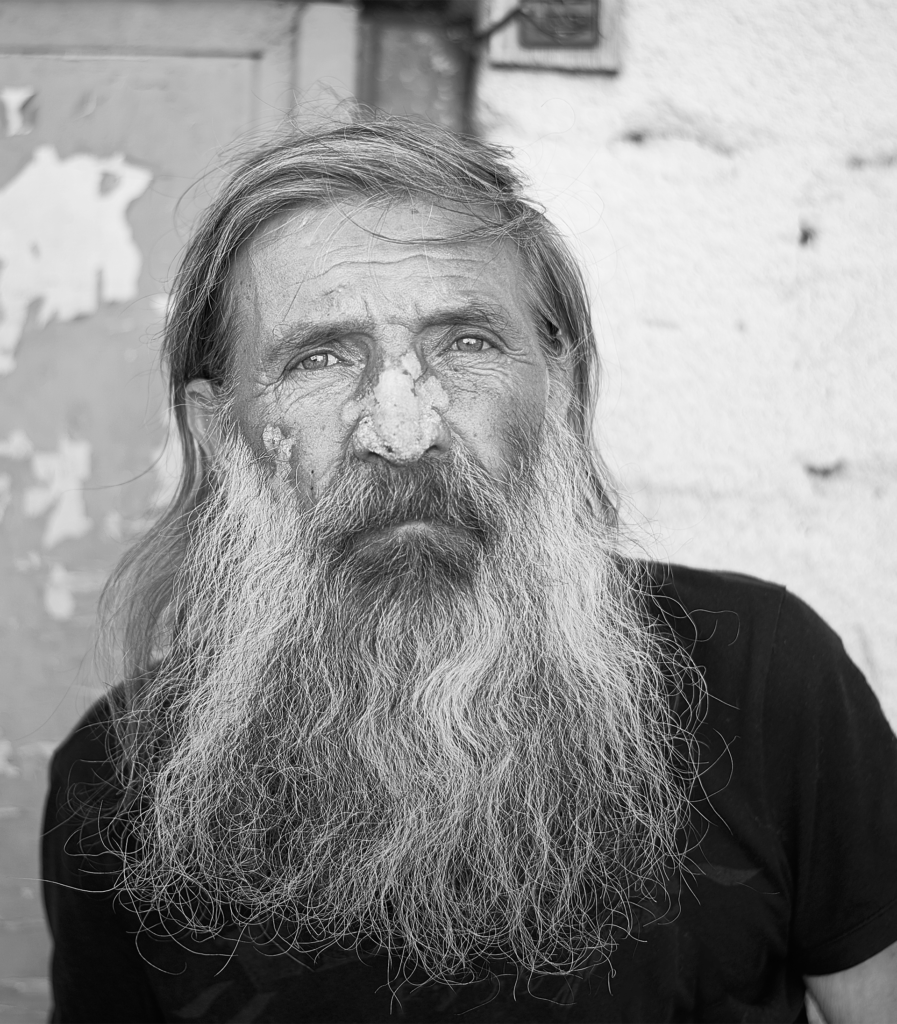

Needs also change for older adults who are experiencing homelessness. The unhoused population’s average life expectancy is 15 to 20 years lower than their housed counterparts. The average age of life expectancy when homeless is 48 years, according to Health Care for the Homeless. Unhoused individuals are also twice as likely to have a heart attack or stroke. Additionally, being sick can lead to homelessness. Medical debt is the leading cause of personal bankruptcy filings in the United States; illness can lead to housing insecurity and individuals becoming unhoused later in life. This is one contributing factor leading to the graying of America’s unhoused population.

The unhoused population’s average life expectancy is 15 to 20 years lower than their housed counterparts.

Last month, INELDA’s executive director Douglas Simpson and I found ourselves in the 103-degree heat of Phoenix for the 2024 National Health Care for the Homeless Conference and Policy Symposium. I mention the heat because while we were able to participate in the conference due to the building’s air conditioning, I was regularly considering the people I saw unhoused situated on the hot pavement around the city during our stay. Death can occur anywhere and for many reasons, but as weather conditions exacerbated by climate change intensify, the needs for those experiencing homelessness are increased.

Needs also change for older adults who are experiencing homelessness. The unhoused population’s average life expectancy is 15 to 20 years lower than their housed counterparts. The average age of life expectancy when homeless is 48 years, according to Health Care for the Homeless. Unhoused individuals are also twice as likely to have a heart attack or stroke. Additionally, being sick can lead to homelessness. Medical debt is the leading cause of personal bankruptcy filings in the United States; illness can lead to housing insecurity and individuals becoming unhoused later in life. This is one contributing factor leading to the graying of America’s unhoused population.

Exclusionary housing policies, incarceration, and systematic racism have also led to a disproportionate number of African Americans experiencing homelessness. Additionally, according to a National League of Cities report, Native people may account for approximately 10% of the homeless population, vastly out of proportion with their demographic presence. The report states: “A lack of affordable housing is tied to higher rates of homelessness in general and on Tribal lands.” The needs of these growing aging populations, and the needs of other people who are traditionally maligned, face unique challenges, including current models of medical care not meeting their basic needs and the frequent presence of compounding comorbidities.

According to the National Alliance to End Homelessness’ report in 2023, 138,098 adults over the age of 55 were counted as homeless. These numbers are collected during a one-day, unduplicated count of sheltered and unsheltered homeless individuals and families across the United States. This is referred to as a point-in-time count or PIT count. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development requires a count to take place in the last 10 days of January every year.

WHERE DOES THIS FIT INTO INELDA’S VISION?

INELDA’s mission is that all individuals have accessible, equitable, and compassionate deathcare that holistically affirms one’s humanity and supports end-of-life choices. In 2019, we developed our first pro bono training for volunteer doulas at Joshua’s House, a hospice for the unhoused in Sacramento, California. Since that time, 20 doulas have been trained to support the hospice.

In 2021, INELDA was approached by Kaki Marshall, an advocate for the unhoused and INELDA-trained doula, who proposed an approach to support those in need by creating an end-of-life care curriculum to educate those delivering care. The proposal also included an approach to document individuals with both current and previous lived experience to inform how the curriculum could be most successfully received and delivered. These voices are at the heart of the approach.

In January of 2024, INELDA was awarded a grant through the McElhattan Foundation to address end-of-life education in Pittsburgh and western Pennsylvania for care facilities and others offering direct support to people experiencing homelessness. A fortuitous encounter at The Coalition to Transform Advanced Care’s doula mixer connected INELDA with a team member at McElhattan Foundation.

MORTALITY DATA

When the majority of us die, the information on how and where we die is recorded by the jurisdiction we live in. This is not always the case with those who die when experiencing homelessness. There is no national repository of data that designates who was unhoused at the time of death. According to the Homeless Mortality Data Workgroup, a project of National Health Care for the Homeless Council (which INELDA is a member of), there were 68 cities and counties who recorded the deaths of people experiencing homelessness as of 2018.

These death counts and data are “collected from a combination of local news reports, medical examiner office and coroner findings, through a public records request, and direct correspondence with local organizers of Homeless Persons’ Memorial Day.” Information on death counts is most commonly collected by area advocates, homeless service providers, and members of religious organizations providing support. Even between those actually collecting data, data collection parameters differ, making comparisons challenging from region to region.

WHAT IS INELDA DOING IN PITTSBURGH?

In January 2023, homelessness was declared a public health emergency in Pittsburgh after an increase of 24% in the unhoused population the prior year. The city’s efforts to reduce homelessness in Pittsburgh have understandably concentrated on food, housing, health care, social services, and mental and substance abuse treatment. Data on the unhoused was grouped together in the region of Pittsburgh, McKeesport, Penn Hills, and Allegheny County.

While PIT counts are thought to underrepresent the actual number of unhoused people by 2.5 to 10 times, the numbers for those living unhoused in the denoted region this January represented 1,026 individuals. The largest subgroup by age was 223 people between the ages of 43 and 53. Additional data showed 163 individuals accounted for between the ages of 55 and 64, and 63 people over the age of 64. So what does this mean for the aging, unhoused population when there is little system in place to address end-of-life needs? Pittsburgh is not alone in this—there are no citywide examples that exemplify how to best support the unhoused at end of life. (There are some wonderful examples of hospices for the unhoused stepping in to address this gap in places such as Salt Lake City and Chattanooga, Tennessee, as well as great palliative care delivered in Toronto.)

Throughout the year, we will be reporting on our progress and sharing some of the amazing work done by street teams delivering medical care to the unhoused Pittsburgh population. The city is the home to the founder of the Street Medicine Institute, Jim Withers, where his forward-looking vision more than 25 years ago called for medical care delivered to the people. What would this look like if doulas worked alongside the street teams and delivered support that also met people where they were at—no matter where that was? What if shelters and care providers for the unhoused delivered end-of-life care with a doula approach? How can we as doulas fulfill a gap in care not just for those in a traditional hospice setting, but for some of the most vulnerable in our communities?