Marketing Matters: Turning Statistics Into Stories

by Cloud Conrad

Marketing Matters: Turning Stats Into Stories

by Cloud Conrad

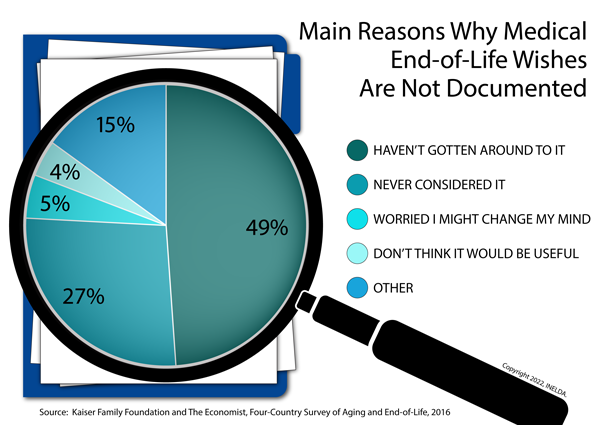

According to research from Kaiser Family Foundation and The Economist, three in four adults have not documented their end-of-life wishes for medical treatment. A 2016 four-country survey of aging and end-of-life care revealed that a little over 25% of all respondents have written down their end-of-life wishes.

Regarding the three in four who haven’t prepared end-of-life documents—why? Half say they haven’t gotten around to it. Over a third of respondents appear either to not know about or to understand why or how to use end-of-life medical care documents. For end-of-life doulas, this presents an enormous opportunity. We know how important these care documents can be, both to a person dying and to their loved ones. By helping give individuals the agency and tools to direct their end-of-life care, with advance care directives and similar documents, we are changing the face of dying.

EOL doulas may offer a valuable contribution to individuals and families by sharing advance care planning information and therefore helping to stimulate conversation and decision-making around the medical spaces of dying. Because documents and medical care are tangible topics, they’re useful in helping create a doorway into the more esoteric, spiritual aspects of dying. Once end-of-life care is in focus, we can expand the perspective by introducing conversations about the nonmedical part of dying—the space that the end-of-life doula occupies.

Storytelling Makes It Personal

An attempt to inform and persuade is the most basic definition of marketing. But before we can change people’s perceptions and inspire them to take action, we must get their attention. A statistic as dramatic as the one above certainly helps get attention, but great messaging can help listeners intuit the “so what”—why they should care.

Humans have strong egocentric tendencies to interpret information by considering how it affects us personally. When we hear stories about others, we often find meaning in those stories by imagining ourselves as the protagonist. If the “so what” is compelling enough, we are able to create our own awareness and may be moved to change our behavior based on what we take away from others’ stories. This is why stories have become such a powerful tool for marketers.

Whether you work for fees or on a pro bono or volunteer basis, when you attempt to persuade others of the value that end-of-life doulas provide, you are a marketer. Stories solidify abstract concepts and simplify complex messages, according to digital marketing powerhouse HubSpot. How, then, might you take a compelling statistic and turn it into a story that moves others to change their own personal “hero’s arc”?

Storytelling Basics

As with fiction writing, the most essential tools for persuasive storytelling are perhaps challenge/tension and achievement/resolution. You don’t need to be a good writer to be a good storyteller. Writers are encouraged to write about what they know, while marketers are encouraged to find topics that their audiences know and can relate to.

Your marketing stories don’t have to have long or complex frameworks, story lines, or characters. In fact, they may not be traditional, linear stories at all, and they don’t require a beginning, middle, and end. You may choose poignant anecdotal evidence from within the communities you serve to support your key points rather than a once-upon-a-time to happily-ever-after approach.

When storytelling to inform and persuade, determining the perspective or point of view you want to use is one of the most critical decisions. Is the story being told in first, second, or third person? Traditional marketing approaches use messaging delivered as second-person imperatives: “Buy this,” “donate here,” “save money,” for example. And we resist being marketed to because imperatives often feel invasive. In contrast, storytelling allows a marketer’s messages to unfold in a non-threatening way. Stories are most often told in first or third person, and the result is usually that an audience is drawn in rather than pushed away.

First-person stories may be confessionals or testimonials in which the teller has walked the walk to earn credence for his or her message. Third-person stories allow the audience to be innocent bystanders and casual observers, invited to create their own awareness. Aesop was a master at this—fables can be stealth teachers.

Another critical decision for storytellers is tone. Tone is essential to foster both the receptivity and willingness of your audience to follow your message and reasoning from start to finish. The right tone can help to draw in your listeners or readers and encourage them to find merit in end-of-life medical planning and extend beyond that line of thinking to consider the merit in nonmedical end-of-life planning—the doula work. Based upon the Kaiser Family Foundation research, here are some ideas to help bring your audience into your story:

Nobody likes to be told they are wrong. Being wrong usually equates to being an outlier and casts that singularity in a negative light. “You did it wrong” messages invite defensiveness and shutter ears, whereas “you are not alone” messages encourage openness. Rather than using messages that suggest that only a few have acted as they should, reassure your audience by pointing out that they are in the majority. This may be as simple as beginning the conversation, the letter, the blog post, or other conveyance with “Like most adults, you may have intended to start this process, or you’ve already begun but haven’t yet completed it for any number of reasons.”

People like to recognize themselves in others. You can use this dynamic to create intrigue, by probing the reasons that three in every four people haven’t codified their end-of-life wishes. Among those who haven’t, almost half do understand why these documents are important and do intend to execute them, this research suggests. Therefore it’s highly likely that this scenario will resonate for your audience. “It’s easy to understand why things have gotten stalled—we are conditioned to avoid discussions about death and dying” can help to assure them that they are not only in good company, but also justified.

Everybody likes to be “in the know” because it makes us feel special. Positioning new information as uncommon information may foster enchantment with the subject matter and send other distractions to the background while you have the attention of your audience. Reinforce this desire for novel information with genuine enthusiasm that suggests you believe that “this new knowledge can support you in making informed decisions.”

Discomfort is a catalyst for change. For those who have never considered advance care planning, do not think it is important, or do not realize these documents could be later revised, you might help them shift their behavior. After casting end-of-life planning concerns in the light they deserve, try creating a before-and-after picture that contrasts users’ inaction with the benefits of determining their end-of-life wishes. A prompt such as“Now that you know the value of this planning…” can help your audience turn ideas into actions.

When you use a storytelling approach to establish yourself as a knowledgeable, credible resource for exploring the end-of-life planning process in a medical context, your audience may be poised to consider you a trustworthy resource to navigate the spiritual end-of-life considerations. Try using the Kaiser Family Foundation’s statistics to start end-of-life conversations in the communities you serve, or find other research that creates a compelling premise for storytelling to persuade. Each time you help foster new awareness about end-of-life planning and doula work, you are changing the face of dying.

It may be counterintuitive to have an audience and not get directly to the point where we overtly “ask for the business” as business owners are conditioned to do. It is also counterintuitive that the hare would lose the race—but we know how that story ended.