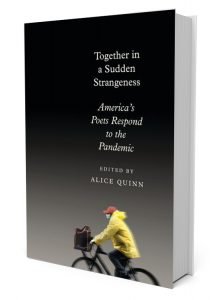

Together in a Sudden Strangeness: America’s Poets Respond to the Pandemic

by Lisa Feldstein

In times of upheaval, the arts help us comprehend events and find meaning. Picasso’s Guernica, for example, conveys the horror of war in a way that news reporting could not. Art can also shock us into an engagement with events by forcefully presenting them in a way we can’t ignore. The 1963 photograph of Vietnamese Mahayana Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức’s self-immolation requires us to witness the lengths to which human beings will go to defend their beliefs.

The Pandemic challenges us in ways we’ve never experienced before: it is a global disaster, the nature of which has paradoxically necessitated we come to terms with it in isolation. Intellectually, we understand that COVID-19’s reach is worldwide, yet experientially we are denied the succor of our communities as we try to make sense of it.

The Pandemic challenges us in ways we’ve never experienced before: it is a global disaster, the nature of which has paradoxically necessitated we come to terms with it in isolation. Intellectually, we understand that COVID-19’s reach is worldwide, yet experientially we are denied the succor of our communities as we try to make sense of it.

Together in a Sudden Strangeness: America’s Poets Respond to the Pandemic (Alice Quinn, ed. Knopf 2020), a collection of more than 100 poems written during the Pandemic, reflects this conundrum. There is no hindsight with which to gain perspective; most of the poems in this collection were written during lockdown. The 100-plus poets are just as bewildered as the rest of us by the sharp, sudden halt to which our society had come. We see our own struggles as these poets try to make sense of streets without people, of formerly cozy rooms that overnight have become prison-like, of death on a scale so vast it is incomprehensible.

In the absence of the tools needed to grasp the Pandemic’s immense scale, the poets describe their evolving understanding of the “new normal” rhythms of their days and grapple with comprehending the world outside the doors they can no longer use. In “April,” Richie Hoffman relates our shared experience of trying to fill the hours of days that feel endless: ‘I spend half the day in the bathtub, trying to read something,/trying to find something to latch on to.’ Billy Collins’ “Sequestration” marvels: ‘No one’s going anywhere,/and they say it’s like this all over/ the rooftops and quarters of the world.’

A few of the poems venture farther. In Mary Jo Salter’s “St. Sebastian Interceding for the Plague-Stricken,” she contemplates the parallels between today and a 15th century plague epidemic. Several poems reference the AIDS epidemic. Sally Wen Mao defiantly challenges anti-Chinese bigotry in “Batshit.” Claudine Rankin’s poem reminds us that the Pandemic also encompassed George Floyd‘s murder and the uprising it ignited.

As a collection, Together in a Sudden Strangeness does a wondrous job of reflecting this epoch back to us. The poems are structurally diverse – everything from sonnets to prose poems to the pastoral – but all are elegies. Individually and collectively, the poets capture the sense of disbelief so many of us lived with in the early months of the Pandemic, when ‘we almost have to stop living in order to save our lives.’ (from “Pandemicon” by Diane Seuss). These are poems to contemplate, to read aloud, to console, to enrage. They capture the new ways of connecting through this time: on Zoom, from apartment windows, standing in driveways. One poem to which I’ve returned several times depicts a supermarket during a Seniors First Hour, in which the socially distanced shoppers dance to the early 1960s songs playing over the store’s speakers. (from “Elder Care” by Ron Koertge) It reminds us that we still have joy.

Collectively, these poems help us understand that even in our isolation, we have not lost one another. Our individual, isolated lockdown experiences are those of our friends and neighbors. Implausibly, we are building shared memories. Our society remains connected through its intricate mycelium – we cannot hold one another, but those fragile, invisible strands continue to link us.

Aubade

Can you hear dawn edging close, hear ⁎ soft light with its vacuum

fingertips ⁎ gripping the bedroom wall, an understated ⁎ what?

exhilaration? Can you hear the voices, ⁎ if they can be called voices,

of towhees ⁎ scratching in the garden and then ⁎ the creaky low

husky ⁎ voice flecked with sleep beside you in bed ⁎ telling a dream

slowly as though in real time, ⁎ and now, interrupting that dream,

can you ⁎ make out the voice, if it can be ⁎ called a voice, of absence

speaking ⁎ intimately to you, directly, ⁎ using the names of those who

were vulnerable, ⁎ those who have gone ⁎ I know you must ⁎ hear it

feelingly, a low vibration in ⁎ your bones, for don’t you find yourself ⁎

absorbed in a next moment beyond your given life?Forrest Gander