Media of the Month – The Anatomy of Grief

The Anatomy of Grief

by Dorothy P. Holinger, Yale University Press (2022)

In her book The Anatomy of Grief, Harvard psychologist Dorothy P. Holinger uses humanistic and physiological approaches to describe grief’s impact on the bereaved. Taking examples from literature, music, poetry, paleoarchaeology, personal experience, memoirs, and patient narratives, Holinger describes what happens in the brain, the heart, and the body of the bereaved.

Readers will learn what grief is like after a loved one dies: how language and clarity of thought become elusive, why life feels empty, why grief surges and ebbs so persistently, and why the bereaved cry. Resting on a scientific foundation, this literary book shows the bereaved how to move through the grieving process and how understanding grief in deeper, more multidimensional ways can help quell this sorrow and allow life to be lived again with joy. The Anatomy of Grief, published by Yale University Press, is now available in paperback.

Excerpt from The Anatomy of Grief:

MOTHERS

My mother is dead, and I want her back. —Meghan O’Rourke

What is motherness? Mothers, however portrayed—as Byzantine Madonnas, mercurial presences in fairy tales, or emancipated professionals in contemporary fiction—embody an essence, a relationship, that is hard to capture with mere words. After birth, a baby listens, stares at, and smells the unique scent of mother while cradled in her arms. No matter the relationship later, a mother’s presence, like air, can seem imperceptible…until you need it to breathe. From always there, to there no more—not gone for a while, but gone forever—a mother’s death is unfathomable. Just as at birth it is the umbilical cord between mother and child that is cut, at death it is the emotional cord between mother and child that is severed forever. Even if one’s relationship with one’s mother began at adoption, not at birth, and even if estrangement has blown stormy winds into the mother-child relationship, she is there until she dies. No matter how a mother’s life ends—peacefully, tragically, unexpectedly, or heroically—her death is the final cut.

My Mother’s Ides of March

Even when our grief about a long-ago death seems to have faded, something can happen that will make it reemerge unexpectedly. Grief can surface in dreams, be displaced into physical symptoms, and cripple relationships, because it never goes away completely, it just stays dormant. Julian Barnes writes of grief: “We may think we have beaten it, when it has only gone away to regroup.”

March 15 was my mother’s birthday. So many times when I was growing up, I would hear my mother say: “I was born on the ides of March, the day Caesar was killed.” For me, the day of her birth became a haunting link to the death of Caesar. Just as Caesar’s death was foretold, so it seemed that my mother predicted her own death.

In Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Caesar hears the prediction, warning him three times:

Caesar: Who is it in the press that calls on me?

I hear a tongue shriller than all the music

Cry “Caesar.” Speak. Caesar is turned to hear.

Soothsayer: Beware the ides of March.

Caesar: What man is that?

Brutus: A soothsayer bids you beware the ides of March.

Caesar: Set him before me. Let me see his face.

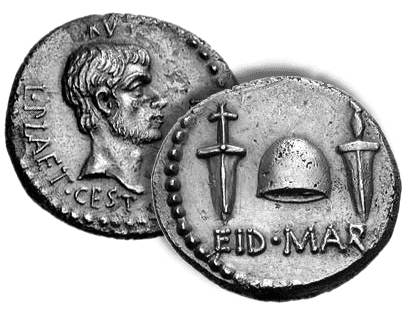

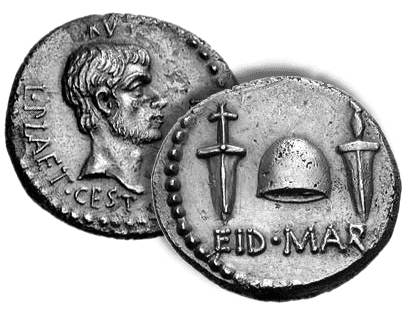

“On the Ideas of March” denarius, depicting Marcus Junis Brutus on one side, and on the other, a pair of daggers and liberty cap representing the assassination of Julius Caesar. Classical Numistmatic Group, Inc. www.cngcoins.com

Cassius: Fellow, come from the throng. Look upon Caesar.

Caesar: What say’st thou to me now? Speak once again.

Soothsayer: Beware the ides of March.

Caesar: He is a dreamer: Let us leave him. Pass.

On that fateful ides of March day, Caesar is stabbed by his senators and bleeds to death on the steps of the Senate. How was my mother able to connect the date of her birth, and the date and method of Caesar’s death, to the way she herself would die? Like Caesar, she bled to death. She endured a procedure meant to restore circulation in her leg, but it went very wrong. Caesar died at the hands of his assassins, but my mother died undergoing a medical procedure intended to help: Although sedated, she somehow managed to pull a stent out of her arm not once, but twice. My husband and I visited my mother the night before her procedure. We also talked with her cardiologist, who was confident and optimistic. A telephone call to me the next afternoon was the first hint of trouble. My mother had pulled the stent tubing out of her arm and could lose her hand if the problem was not corrected. “Give the team an hour,” the cardiac fellow suggested. We didn’t wait, but headed to the hospital. Calling before we left, the news was that things were “back on track.”

At the hospital, the doors to the special procedures room were open. Even though we were told not to go in, I caught a glimpse of my mother on the table. The attending physician said all was proceeding on course, and they would call us in several hours after the procedure was over.

We drove to a cousin’s who lived very close by. As we walked in, she told us the hospital had called to say that the situation had turned critical. We drove back and went immediately to special procedures. No one stopped me this time. The double doors opened, and I walked in to see blood on the team’s shoes and on their scrubs. Although my mother’s arms had been strapped to boards, she had managed to pull out the stent again. The chalky color of her face was in stark contrast to the blood on her arms and the wooden supports to which her arms were fastened. Walking closer, I heard her nearly inaudible moans. I bent down to her and said, “I’m here.” Her response, my dying mother’s last words, was, “Let them let me die.” And I did. I told the team to stop. They wrapped her and wheeled her out of special procedures. My husband and I were told to wait until they had her settled back in her hospital room. In a waiting area, I paced back and forth—innumerable times, it seemed. To my husband, who was sitting down, I said, “She’s dying.”

When we went into her room, it was then that time stopped for me. There was no time. As it had been so long ago with my mother and me, she and I were in a space where time, and even words, did not exist. I was there again with her where there was no conscious thought. It was just me and my beloved mother. Mommy and me together, alone, and I remembered her smiling, how at times she would beam at me, proud of me and delighted to be with me. And the bond from that long-ago time when all that mattered and all that existed for me was my mother: That bond was breaking, that time was ending. I stroked her face, crying, my heart breaking as her heart beat slower and slower. Then her heart stopped beating. The monitors stopped. She was dead. My mother was dead.

It was as if something had fallen off the Earth. My mother’s life was over. I stayed alone with her for a time, stroking her forehead, and crying tears that had no name. I left with a lock of my mother’s hair, cut with scissors a nurse had given me.

To lose one’s mother is to lose the self that once was with her. The lifeline that began with the umbilical cord—or with an attachment surrounding adoption—and developed into a deep emotional bond, has been cut. Yet a mother’s quintessence, the essence of her, internalized first as the child’s idealized image and later as the adult’s more realistic one, can be a source of strength, even in grief. A mother’s very motherness can help mend her son or daughter’s breaking heart, even when she can’t be there anymore.